Rail speed limits in the United States

Rail speed limits in the United States are regulated by the Federal Railroad Administration. Railroads also implement their own limits and enforce speed limits. Speed restrictions are based on a number of factors including curvature, signaling, track condition, the physical condition of a train, and the presence of grade crossings. Like road speed limits in the United States, speed limits for rail tracks and the trains that run on them use miles per hour (mph).

Contents |

Signal speeds

Federal regulators limit the speed of trains with respect to the signaling method used.[1] Passenger trains are limited to 59 mph and freight trains to 49 mph on track without block signal systems. (See dark territory.) Trains without "an automatic cab signal, automatic train stop or automatic train control system" may not exceed 79 mph. The order was issued in 1947 (effective 31 Dec 1951) by the Interstate Commerce Commission following a severe 1946 crash in Naperville, Illinois involving two Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad trains.[2][3][4] Following the 1987 Chase, Maryland train collision, freight trains operating in enhanced-speed corridors have been required to have locomotive speed limiters to forcibly slow trains rather than simply alerting the operator with in-cab signals. The signal panel in the Maryland crash had been partially disabled, with a muted whistle and a missing light bulb.

Following the 2008 Chatsworth train collision in California, a federal law was passed requiring positive train control (PTC) to be implemented nationwide by 2015.[5] While a primary goal of PTC is to prevent collisions, it also increases railroad capacity and fulfills the FRA requirements for increased speeds. However, several competing PTC technologies are being used in different regions of the country, and a clear winner has not yet emerged as of 2010.

Track classes

In the United States, the Federal Railroad Administration has developed a system of classification for track quality.[6][7] The class of a section of track determines the maximum possible running speed limits and the ability to run passenger trains.

| Track type | Freight train | Passenger |

|---|---|---|

| Excepted [us 1] | <10 mph (16 km/h) | not allowed |

| Class 1 | 10 mph (16 km/h) | 15 mph (24 km/h) |

| Class 2 | 25 mph (40 km/h) | 30 mph (48 km/h) |

| Class 3 | 40 mph (64 km/h) | 60 mph (97 km/h) |

| Class 4 [us 2] | 60 mph (97 km/h) | 80 mph (129 km/h) |

| Class 5 [us 3] | 80 mph (129 km/h) | 90 mph (145 km/h) |

| Class 6 | 110 mph (177 km/h) | |

| Class 7 [us 4] | 125 mph (201 km/h) | |

| Class 8 [us 5] | 160 mph (257 km/h) | |

| Class 9 [us 6] | 200 mph (322 km/h) | |

- ^ Only freight trains are allowed to operate on Excepted track and they may only run at speeds up to 10 mph (16 km/h). Also, no more than five cars loaded with hazardous material may be operated within any single train. Passenger trains (in revenue service) of any type are prohibited.

- ^ Most mainline track, especially that owned by major railroads is Class 4 track

- ^ Class 5 track is operated by freight railroads where freight train speeds are over 60mph. On parts of the BNSF Railway Chicago–Los Angeles mainline, the old Santa Fe main, ATS equipped passenger trains such as Amtrak's Southwest Chief can operate at up to 90 mph (145 km/h). This is gradually being reduced as the train stop system is retired, but freight trains over 60 mph still require class 5 track.

- ^ Some of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor has Class 7 trackage .

- ^ Portions of the Northeast Corridor are the only Class 8 trackage in North America allowing for 135 mph (217 km/h) and 150 mph (241 km/h) operation.

- ^ There is currently no Class 9 high-speed rail in the United States.

Curves

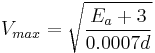

Assuming a suitably maintained track, maximum track speed is limited by the "centrifugal force" which acts to overturn the train. To compensate for this force, the track is superelevated (the outer rail is raised higher than the inner rail). The speed at which the centrifugal force is perfectly offset by the tilt of the track is known as the balancing speed:

where  is the amount in inches that the outside rail is superelevated above the inside rail on a curve and

is the amount in inches that the outside rail is superelevated above the inside rail on a curve and  is the degree of curvature in degrees per 100 feet (30 m).

is the degree of curvature in degrees per 100 feet (30 m).  is given in miles per hour.

is given in miles per hour.

Normally, passenger trains run above the balancing speed, and the difference between the balancing superelevation for the speed and curvature and the actual superelevation on the curve is known as unbalanced superelevation. Track superelevation is usually limited to 6 inches (150 mm), and is often lower on routes with slow heavy freight trains in order to reduce wear on the inner rail. Track unbalanced superelevation in the U.S. is restricted to 3 inches (76 mm), though 6 inches (152 mm) is permissible by waiver. There is no hard maximum set for European railways, some of which have curves with over 11 inches (280 mm) of unbalanced superelevation to permit high-speed transportation.[8]

The allowed unbalanced superelevation will cause trains to run with normal flange contact. The points of wheel-rail contact are influenced by the tire profile of the wheels. Allowance has to be made for the different speeds of trains. Slower trains will tend to make flange contact with the inner rail on curves, while faster trains will tend to ride outwards and make contact with the outer rail. Either contact causes wear and tear and may lead to derailment if speeds and superelevation are not within the permitted limits. Many high-speed lines do not permit the use of slower freight trains, particularly with heavier axle loads. In some cases, the wear or friction of flange contact on curves is reduced by the use of flange lubrication.

See also

References

- ^ United States Code of Federal regulations Title 49 - transportation, subtitle b - other regulations relating to transportation, chapter ii - federal railroad administration, department of transportation, part 236 - rules, standards, and instructions governing the installation, inspection, maintenance, and repair of signal and train control systems, devices, and appliances commercial database

- ^ "Ask Trains from November 2008". Trains Magazine. December 23, 2008. http://www.trains.com/trn/default.aspx?c=a&id=4424. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ William Wendt (July 30, 2007). "Hiawatha dieselization". Yahoo Groups. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/steam_tech/message/54227. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ John Gruber and Brian Solomon (2006). The Milwaukee Road's Hiawathas. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0760323953.

- ^ U.S. Rail Safety Improvement Act of 2008, Pub.L. 110-432, 122 Stat. 4848, 49 U.S.C. § 20101. Approved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Federal Railroad Administration Track Safety Standards Compliance Manual, Chapter 5 Federal Railroad Administration Track Safety Standards Compliance Manual" (PDF). United States Government. 2007-04-01. pp. 155. http://www.fra.dot.gov/downloads/safety/tss_compliance_manual_chapter_5_final_040107.pdf. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ "Federal Railroad Administration Track Safety Standards Compliance Manual, Chapter 6 Federal Railroad Administration Track Safety Standards Compliance Manual" (PDF). United States Government. 2007-04-01. pp. 101. http://www.fra.dot.gov/downloads/safety/track_compliance_manual/TCM%206.PDF. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ Zierke, Hans-Joachim. "Comparison of upgrades needs to recognize the difference in curve speeds". http://Zierke.com/shasta_route/pages/05curve-curve.html. Retrieved 2008-04-10.